‘I feel so let down by Canada’: Radiohead and drum tech’s parents demand answers in his Toronto death

By Katie Nicholson, CBC News (November 29, 2017)

The mangled debris in the north Toronto park looked more like a tornado had touched down than the remains of a stage.

Metal alloy pipes meant to withstand thousands of kilograms of pressure buckled and lay tangled around keyboards like spaghetti. Trapped crew members cried out for help from among the smashed lighting grids, motors and expensive audio equipment

In the mess of bent and broken scaffolding, destroyed lights and instruments, a pair of legs stuck out from beneath a 2,270-kilogram video monitor that had been suspended from the ceiling.

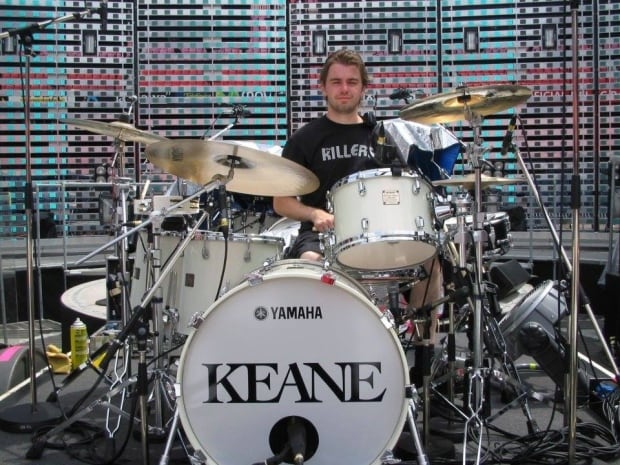

The coroner concluded that Scott Johnson, a drum technician for the British rock band Radiohead, was killed instantly.

Johnson was killed instantly in the collapse. (Richard Young)

Five years later, there are no answers as to how the collapse happened and no one has taken responsibility for the June 16, 2012, incident at Downsview Park. Charges in the case were stayed in Ontario Court of Justice in September.

But CBC News has learned the chief coroner of Ontario will hold an inquest into Johnson’s death, a long-awaited move to be formally announced Thursday.

Radiohead had been in contact with Ontario officials seeking an inquest, wanting to use its influence to pressure authorities to get answers and some small measure of closure for the drum technician’s parents, Ken and Sue Johnson

“I would like to know who made mistakes, what the mistakes were and mostly to make sure that it doesn’t happen to someone else because it cost my Scotty’s life,” said Sue Johnson.

Behind the scenes, Radiohead’s management and the Johnsons have been meeting with British MPs who have, in turn, written letters to the Canadian High Commission demanding something be done.

Burden of responsibility

Radiohead drummer Philip Selway feels a burden of responsibility to Johnson’s parents.

“When the collapse happened, it happened at four in the afternoon. Our soundcheck was due to start at four and I actually should have been where Scott was.” Selway said.

“That is an incredible weight, and personally I can’t let this lie. I want to see a proper conclusion, something that is respectful to Scott.”

Things were running a little behind schedule that day. The band, which had played in Montreal the night before, was sequestered a short distance from the scaffold stage when it happened.

Radiohead drummer Philip Selway had been scheduled to be on stage at the time of the collapse, in the position where Johnson was when he was killed. (Gary Solilak/CBC)

“We heard what sounded at the time like an enormous cabinet of glasses falling over,” Selway said. “You could see it from behind that the top of the structure had buckled.”

Time dragged as the band anxiously waited for news about the crew until at last they were told the tragic news.

“Something that was meant to bring a lot of joy that evening had just resulted in the death of Scott,” Selway said.

It took a year for Ontario’s Ministry of Labour to conclude its investigation.

Legal case collapsed

Live Nation, Optex Staging & Services and the engineer hired to design the stage were charged with 13 offences under Ontario health and safety laws. Proceedings began in Ontario Court of Justice in 2013. All three defendants pleaded not guilty.

But like the stage, the case would also collapse.

With only three days left in the trial, the original judge, Shaun Nakatsuru, was appointed a judge in Ontario Superior Court of Justice. Because of the appointment, he said he no longer had jurisdiction to preside over the rest of the proceedings and was forced to declare a mistrial.

The newly appointed judge, Ann Nelson, ruled in favour of the defendants’ application to have the case dropped under the Jordan ruling. That landmark 2016 Supreme Court of Canada decision set strict timelines to ensure that an accused person’s charter right to a trial without unreasonable delays is upheld.

More than five years after the collapse, an inquest is to be called into Johnson’s death. (Ken Johnson)

The previous judge, Nakatsuru, had denied a similar motion.

Because the new trial would not have concluded until May 2018, Nelson ruled in September 2017 that the defendants’ charter right to be tried within a reasonable time would have been violated. All charges were stayed, effectively killing the case.

Watching it unfold from across the pond, Selway said the decision disgusted and nauseated him.

“We’re just appalled that this has been allowed to conclude in this manner. I feel angry about it.”

Heavy loss

Loss hangs heavy in Ken and Sue Johnson’s South Yorkshire cottage. Scott Johnson was their only child.

“We were like partners in crime,” his mother said. “Sometimes I’d like just to be able to hold him and smell him.

“We both absolutely loved snow. And when it snows, it kills me now.”

Their son’s death was hard enough for the couple but the lack of answers has also angered and frustrated them.

“The word ‘stayed’ — it’s so offensive to me,” Ken Johnson said. “It seemed a fundamental basic to us that the truth would come out. It was not something that we worried about.”

Johnson’s father, Ken Johnson, says the word ‘stayed’ is ‘so offensive to me.’ (Gary Solilak/CBC)

Sue Johnson is critical of the decision to apply the Jordan ruling in her son’s case.

“To sort of think that it’s bad for the people that are being accused, I would like them to sit in our shoes because it’s five years, and five years that’s been the most horrendous five years of my life. I feel so let down by Canada.

“They seem to have forgotten Scott in all this,” she said. “They seem to forget that Scott lost his life because somebody made a mistake.”

Ken Johnson is pleased there will be an inquest, but says what he’d really like to see is the court case reopened.

‘It just wasn’t strong enough’

It is a cruel irony that he is, by trade, a scaffolder who writes the annual safety report for the United Kingdom’s National Access and Scaffolding Confederation.

“Some of the errors are fairly obvious because of the nature of my role. It just wasn’t strong enough. There’s no getting away from it. If it was strong enough, it would have stayed up.”

That was one of the main underpinnings of the Crown’s case.

According to court transcripts, prosecutor Dave McCaskill, buttressed by several bankers boxes of evidence from the Ontario Ministry of Labour’s year-long investigation into the collapse, set out to prove that the engineer “miscalculated the total gross weight of the stage roof and its attachments” by approximately 7,260 kilograms.

Sue Johnson can’t help but think the courts didn’t take her son’s death seriously. (Gary Solilak/CBC)

The Crown also intended to show that Optex did not follow the engineer’s drawings, noting that “discrepancies between the design and drawings and what was actually constructed on site profoundly contributed to the structural failure.”

Final arguments were never heard, but during the case, Live Nation argued it did not construct the stage and that it believed it had hired competent people. Optex Staging and Services did not have legal representation. For his part, the engineer blamed Optex for not putting the stage up properly.

In interviews with CBC, Optex owner Dale Martin and the engineer, Domenic Cugliari, expressed regret about Johnson’s death. Both had pleaded not guilty to the charges.

Cugliari declined further comment because he is under investigation by the Professional Engineers of Ontario in connection with his role in the matter.

No national standards

Live Nation, which according to the Crown was responsible for organizing the Downsview concert, “including providing construction equipment and the labour required to construct the stage,” left a voice mail for CBC saying it would not comment on the matter.

There are no national standards governing temporary structures in Canada, and the Ontario Ministry of Labour has not made any of the findings of its investigation public.

Questions to the Labour Ministry regarding the Radiohead case were referred to Ministry of the Attorney General, which has not granted CBC’s request for an interview.

The Ontario Ministry of Labour spent a year investigating the collapse. (Richard Young)

Doug Perovic, a professor and forensic engineer at the University of Toronto, worries that a lack of accountability and a lack of public findings and information about the case make it possible another such collapse could happen.

“Scientists, engineers are hardwired to want to get the answers. We want to solve the problem, find the answers and ultimately prevent such things from happening again, potentially improve safety codes and standards.” Perovic said. “It’s very frustrating that this sort of got hung up and just stopped.”

Perovic has reviewed numerous workplace fatalities over the years, including the Downsview collapse.

“Canada’s response to … failures of this type, collapses, workplace accidents, I think needs to be improved.”

‘A failing in the legal system’

Sitting in her living room, Sue Johnson can’t help but think the courts didn’t take her son’s death seriously.

“I wouldn’t have wished it on any of the lads but if it would have been [a member] of Radiohead, would the outcome have been different?” Johnson wondered.

It’s a thought that has crossed Selway’s mind. He and the band are determined to use their name recognition to help the Johnsons get answers.

There are no national standards governing temporary structures in Canada. (Richard Young)

“To actually have the ability and kind of a platform when we have been let down by the legal system to actually throw a spotlight on this process, that is incredibly important,” Selway said.

“There’s been a failing in the legal system.”

In letters to the Canadian High Commission, the British Culture Minister Ed Vaizey and Ed Miliband, the Labour MP for Johnson’s home riding of Doncaster, pushed for the Ontario government to do more to seek answers and accountability for the collapse.

“I am writing to you to urge you to bring all possible pressure to bear in seeking on my constituent’s behalf answers for the tragedy of his son’s life,” Miliband wrote.

Although the inquest’s conclusions won’t be binding, its recommendations, if implemented, could be used to help prevent further incidents.